When I was five or six years old a teacher at my school died—a heart attack as I recall. I can’t remember her name, but most of the women in my life were teachers, including my grandmother, so I was taken out of school to attend her friend’s—this teacher’s—funeral.

I’d attended my great-grandmother’s funeral but was four when she died and don’t remember much—tall people crying, getting stepped on once, the smell of perfume and makeup. Around the same time, I attended my great-aunt’s funeral and two-great uncles’, all of which are as clear as Boggy Creek’s brown water. But this funeral was different and had a profound impact on me.

This funeral was large. So large in fact, it wasn’t held at the local funeral home, but inside a Methodist church in Beaumont. The service was early in the morning, and the sun cast towers of light—pillars—westward, across the pews and people. One rested squarely on the open casket. My grandmother held my hand as the organ played, and we walked in shuffling line with others to view the body.

After so many funerals—family, friends, fellow Marines, old vets, others—I should know what that part of the service is called, but I don’t. Looking at the body for the last time, that is. There’s time for viewing, when it’s an open casket of course, but then there’s the pass in review. Pass in review. A military drill movement where a parade of troops passes in formation, before their commander. I have performed the maneuver, or more accurately, participated in the maneuver, dozens—hundreds—of times and that is all I can think to call it.

I felt the weight of her dead body as we made the long walk to her. She was swelling. Not literally, but her presence. In the room. In me. I forced myself to trudge through a thickening. I forced myself to look up and into the casket, to look at the imitation lying there, surrounded by folds of silk and varnished wood. She looked sunken and cold. Thin-lipped and caked. Was she perfumed or was that my grandmother? Some other woman perhaps? I snuck my right arm into the casket and poked her right hand while my grandmother held my left.

I’d cleaned dead things with my hands by that time, but they give warmth. Her body. That touch. It sucked the warmth from me, and I felt the bones in my grandmother’s hand just then. I grew cold all over and pulled away from her and began to cry.

“It’s okay, Son. She’s in Heaven,” my grandmother said. “What matters, her soul, is in heaven. This is just her body. There’s nothing to be afraid of.”

I wish I had spoken with her about that moment later in life. We had hard conversations as the years passed. Conversations about death. Conversations about her death. About the body. The Soul. But I didn’t. I never told her it wasn’t the teacher lying there, or touching a dead hand, or even the fear of dying itself that made me pull away. That scared me. It was a young boy’s realization that she would die. That one day I’d need to touch her hand too.

Years later, I observed her pass in review. It was a small affair compared to her friend’s, but I watched person after person make the long walk to her body, knowing my walk would be at the end, reserved for close family. It was maybe fifteen feet from the pew where I sat to her, but it might as well have been fifteen hundred. And the swell—that thickening—was there. Pushing against me like an undertow in the wrong direction while another pulled. Toward and away from the inevitable. Toward and away from goodbye. Toward and away from touching her hand.

I forced myself to walk to her. I forced myself to hold her hand. Cold. Thin. Rigid. In that way—the only way I can think of—she was unremarkable.

It’s okay. Heaven, soul, body. There’s nothing to be afraid of. I can still hear her saying it.

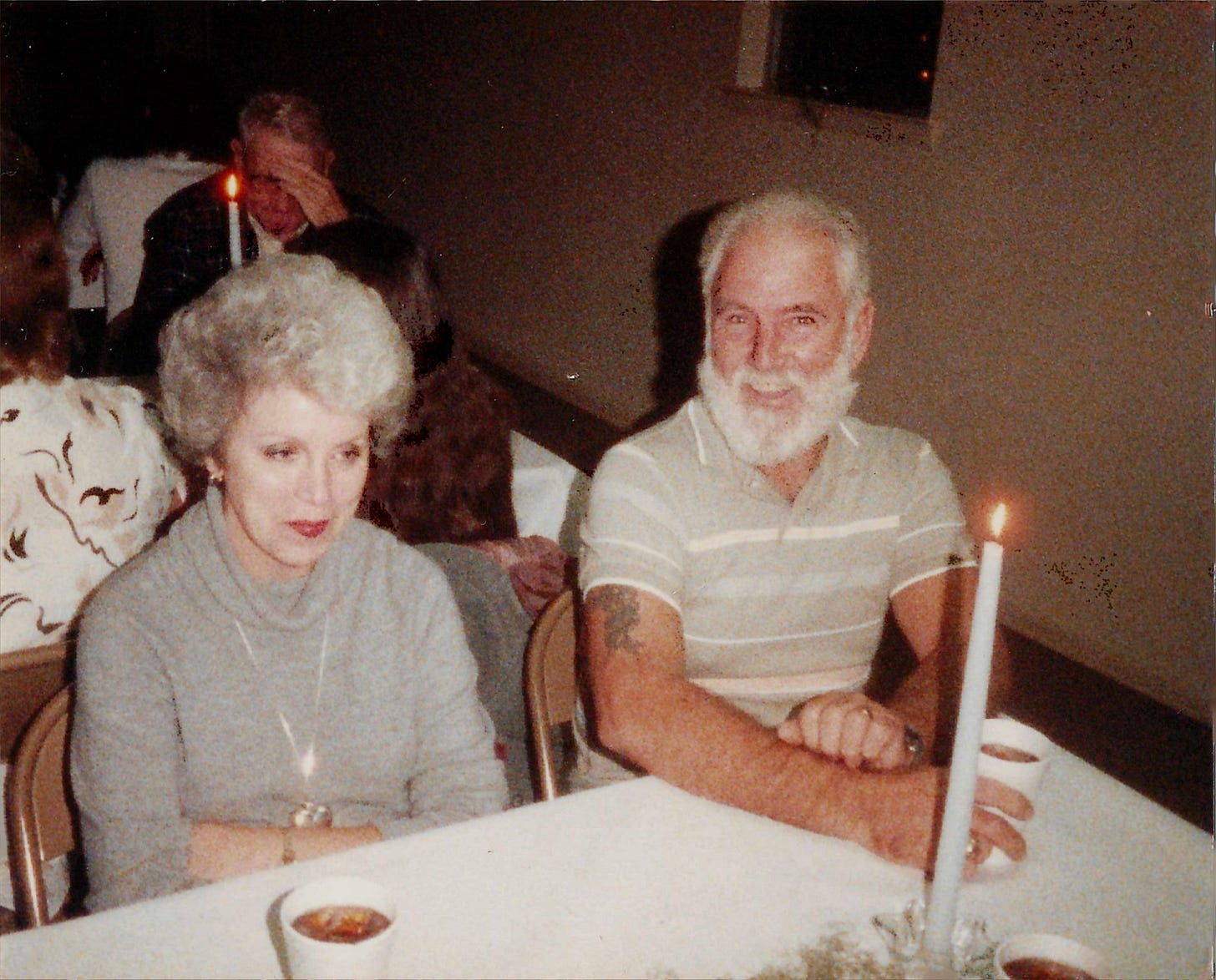

I make the long drive to Vidor, Texas tomorrow from where I’m sitting right now. One thousand seven hundred seventeen miles and another long walk—the exact same fifteen feet. To fold my grandfather’s flag. To force myself—my forty-two-year-old, five-year-old self—to hold his hand. To pass in review again.

Well done, Aaron

I accepted that flag with a humble and contrite heart. I am both honored and grateful that it was a man of your caliber to be the one to put it in my hands. You, Your Grandmother and my Father will always have a home in my heart. Be well, my friend. Always.