Cormac McCarthy’s novel, The Road1, and Suzane Collins’, The Hunger Games2, are exceedingly successful by almost any matrix, and they share literary themes which contribute to their respective popularity and commercial success. In truth, they mirror each other in numerous ways which expand their audiences and promulgate success. In the case of The Road, it earned the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and was built on a foundation of acclaim that McCarthy’s previous works had garnered from littérateurs and scholars alike. With respect to The Hunger Games, it earned the Dorothy Canfield Fisher Children's Book Award and accompanied The Road to Hollywood where both would be successfully adapted into films— the former expanding into a series which includes four films, to date, and another round of prequels in production as of this essay’s publication. Academia offers a demonstrable argument for its role in the novels’ exposure to, and popularity with, an ever-expanding audience of readers— they have been taught in primary, secondary, and undergraduate education programs for years, and that is likely to continue3. This essay will analyze another factor which contributes to their popularity and success, more nuanced and less scrutinized than the best-seller lists or an educator’s required reading, or even box office earnings. A comparative analysis of The Road and The Hunger Games, supported by an evaluation of metaphor, presents a theme echoed in them both, about the child protagonists being more than proletariat rebel or apocalyptic sojourner, but as anointed messenger and divine authority— as child (M)messiahs.

So why do Collins4 and McCarthy5 create messiahs for their stories? Why not just pen a rebel and a sojourner? And what makes them different from one another? Part of the reason has to do with contemporary events that influenced both authors to write their novels in the first place. It is true both were written in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks in 2001, but much of the reason has to do with the authors’ family life. In both cases, the authors’ respective influences and the world in which they live are transferred to the purpose and behavior of their protagonists.

For Collins, her childhood influenced the novel’s message more than any other factor. Her father was in the United States Air Force and served in the Vietnam War. Collins was six when he deployed to Vietnam. He suffered from suffered from post-traumatic stress, and Collins recounts that for years afterwards, his cries would sometimes wake her up. The family was stationed in Europe after the Vietnam War ended, and they would tour places that her veteran father saw through a different lens than a casual tourist might. Collins describes visiting a castle with him, “which she imagined would be ‘fairy-tale magical,’ [but it] turned into a lesson on fortresses”6. Intimate connections with the psychological repercussions of war, continuous exposure to and study of military conflict, and the impact each of those has on the adolescent psyche were paramount in the novel’s genesis. Collins is on record stating that “‘[she does not] write about adolescence. [She] writes about war. For adolescence’” (Dominus). The Hunger Games thereby offers Collins’ readers a unique kind of war to observe— one without formal battle study or campaign maneuvers— but one which also, when narrated by a child messenger, affords a developing mind enough space to understand and recognize its messages. Through this process, Katniss Everdeen becomes a metaphorical messenger of war— a messiah.

McCarthy is a veteran of the United States Air Force, himself, though his experience as a father— particularly as an older father— was more significant for The Road’s development than military service. After winning the Pulitzer Prize and being selected as book of the month for Oprah Winfrey’s book club, the talk show host was able to secure a rare interview (his first television interview)7 with McCarthy. When asked about the origin of the novel, McCarthy described being alone with his son one evening, and looking out over a desolate El Paso, Texas. He says that he imagined the place in “fifty or one hundred years… [with] fires up on the hill and everything being laid waste,” (Winfrey) and goes on to say, “and I thought a lot about my little boy…” (Winfrey). When pressed, McCarthy reluctantly confesses, that the novel is a love story to his son and without his son’s birth coming at that time in his life, “it never would have occurred to me to try and write a book about a father and a son” (Winfrey). McCarthy explains that having a child at an elderly man, “forces the world on you” (Winfrey). Thus, the boy in his novel becomes more than a fictionalized character. He represents a metaphorical savior for McCarthy— for humanity— a Messiah.

Metaphor has been mentioned several times related to the young protagonists, but others exist which support the idea of their respective roles as (M)messiah. One such metaphor would eventually become the title of Collins’ conclusion to The Hunger Games series, the mockingjay. This fictional creature is a result of one of the Capitol’s “muttations,” (42) jabberjays, mating with mockingbirds. The jabberjay was a weaponized mutant-homing bird which relayed rebel intelligence to the Capitol. In return, the rebels used the same creature to weaponize mis- and disinformation and advance their cause. After the rebellion, mockingjays become prevalent and possess a supernatural ability to detect righteousness in a person by way of that person’s singing and anthropomorphically bestows upon them a degree of respect. Katniss makes it clear that this is a selective offering and that “Not everyone is treated with such respect” (43). Where her father had a “voice that was beautiful, high and clear…,” (43) Katniss does not.

Though her voice is a poor comparison to her father’s, the mockingjays anoint her as righteous and aid her throughout the novel, both saving her life in the games and helping to spread a message of love, mourning, and ultimately rebellion. Katniss and her companion, Rue, use the mockingjays as a signal device so they can communicate without the other tributes discovering their locations. When Rue is killed in the so-called game, Katniss conducts impromptu funeral rites which include a dirge to honor the “sacrificial suffering”8 of her companion, and “Then, almost eerily, the mockingjays take up [her] song” (235). The mockingjay becomes a metaphor for Katniss’ anointment as messenger and elevates her beyond tribute and child-combatant to a child messiah. Similarly, Katniss creates a metaphor herself during the funeral rites, which further cement her as messenger and messiah.

She offers a three-fingered salute to Rue at the conclusion of the funeral scene. The reader understands this to be a sign of respect from earlier in the novel when Katniss volunteers as tribute. As her companion lies dead, victimized by her own authoritarian government, she says: “I feel my impotence… I want to do something, right here, right now… to show the Capitol that whatever they do or force us to do there is a part of every tribute they can’t own” (237). She places flowers around Rue’s corpse and presses “the three middle fingers of my left hand and hold them out in [Rue’s] direction” (237). With this simple gesture, Katniss silently articulates (for a second time) her message— that she— that the oppressed— can resist the totalitarianism of the Capitol. The salute becomes a metaphor from that point on which reflects an indomitable spirit and resistance and is adopted by the followers of a messiah for the coming rebellion.

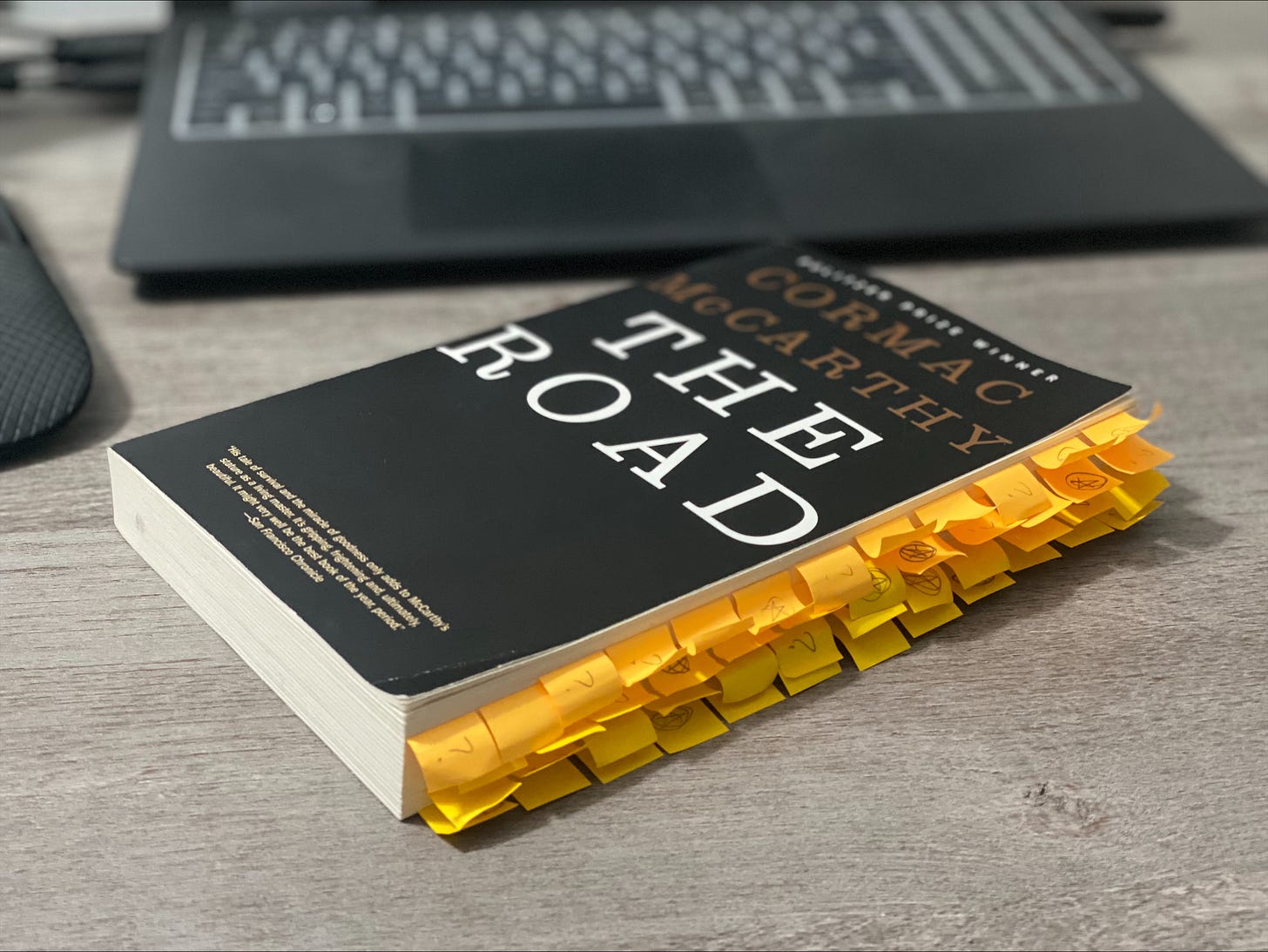

McCarthy’s metaphors are much more on the nose, and yet much more poetic. There at least thirteen denotations to God and fifteen connotations to divinity— most of which are in reference to the boy. That equates to a divine reiteration on every tenth page (1:10.25). Two specific metaphors offered by McCarthy support the boy as an anointed savior and Messiah. The first is related to his anointment directly— a requirement for messianic consideration. The boy’s father prepares a resting place in the sand for his son and holds him while he sleeps, then the father “tousled his hair before the fire…” (74). The father refers to these actions as “forms” (74) and says that they become “ceremonies out of the air,” (74) by which the boy begins his transition. The father says as much when he declares the ceremony an “ancient anointing;” (74) however, McCarthy uses the boy’s anointed hair as a metaphor for his Messianic nature. After the ceremony, the father “… stroked his pale and tangled hair. Golden chalice, good to house a god,” and the boy’s ascension is recognized and complete.

Lydia R. Cooper’s essay, “Cormac McCarthy’s The Road as Apocalyptic Grail Narrative,”9 points to a passage where the father sees his son, “glowing… like a tabernacle,” (273) which in ancient Israel would have been used to “[house] the presence of God” (224). With McCarthy’s use of a tabernacle as metaphor, Cooper asserts that the boy becomes a “vessel” (224) for “the essence of divinity within him” (224). In one passage, the father makes his beliefs perfectly clear when he says, “If he is not the word of God God never spoke” (5). In the father’s mind, the boy himself is a metaphor, who is to be protected, so that he can spread the word of God after the father dies. Though more than two dozen additional allusions are made, these present the boy as more than a post-apocalyptic sojourner; he is—from the time of his anointment— a Child Messiah.

In both novels, Collins, and McCarthy layer numerous themes to create meaningful and relatable works. They tap into societal concerns related to war and its impact on young people, which at publishing, The Road and The Hungers Games had observed for five and seven years respectively through the American coined, “Global War on Terror.” Both Collins and McCarthy, draw on emotionally relevant aspects of youthful rebellion and paternal and maternal instincts (thought he latter is arguably absent in The Road) to protect their children. And finally, both Collins and McCarthy complement these literary moves by using metaphors which all readers, from adolescent to adult, can recognize and interpret. These become force multipliers and result in ultra-popular works of fiction among readers and fans of cinema alike and garner enormous literary, academic, and financial success. But they do something more as well.

Collins and McCarthy pen characters that—because of their role within the story—because of a shared messianic theme— are equal parts relatable and unattainable to the unanointed masses. The young protagonists become our heroes, and our messengers, and our imagined saviors. They become the people we want to be and the children we hope we have, and so we are endeared to them as characters, certainly, but also as the embodiment of real ideas that we strive to live up to. They become child (M)messiahs, and we begin to worship them for it.

Editorial note: This essay was originally submitted online for LIT-322-H6176 at Southern New Hampshire University on 8 Aug 2023.

McCarthy, Cormac. The Road. First Vintage International Edition ed., Vintage International, 2006.

Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. Scholastic Press, 2008.

Saunders, Jane M. “What The Hunger Games Can Teach Us about Disciplinary Literacy.” The English Journal, vol. 103, no. 3, 2014, pp. 42-43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24484152. Accessed 14 July 2023.

Cunningham, John M.. "Suzanne Collins". Encyclopedia Britannica, 6 Aug. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Suzanne-Collins. Accessed 2 September 2023.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Cormac McCarthy". Encyclopedia Britannica, 16 Jul. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cormac-McCarthy. Accessed 2 September 2023.

Dominus, Susan. “Suzanne Collins’s War Stories for Kids.” The New York Times, 8 Apr. 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/10/magazine/mag-10collins-t.html

Winfrey, Oprah, and Cormac McCarthy. “Cormac McCarthy Interview on the Oprah Winfrey Show.”

Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

Murphy, Sarah Outterson, and Mary Pharr. “The Child Soldier and the Self in Ender’s Game and The Hunger Games.” Of Bread, Blood, and The Hunger Games: Critical Essays on the Suzanne Collins Trilogy, McFarland & Co., Jefferson , NC, 2012, pp. 201–202.

Cooper, Lydia R. “Cormac McCarthy’s The Road as Apocalyptic Narrative.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 43, no. 2, 2011, pp. 218–236. Summer 2011. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41228678