Wise Men, Good Men, Wild Men, Grave Men

Discerning meaning in the poetry of the bereaved

What message does a particular literary work convey? Literary critics have assumed the role of oracle and weigh content and context on behalf of the layman and proffer meaning for all. They glean literary artifacts through the lens of a particular critical approach to literature and, in doing so, presume a message within a text— the necessary meaning of a text. Ross C. Murfin writes, in part, that “deconstruction has a reputation for being the most complex and forbidding of contemporary critical approaches to literature…” That may be so, however, complexity is not synonymous with incomprehensibility, and a forbidding thing does not equate, necessarily, to being an inaccessible thing. Literature and poetry facilitate an author’s presentation of tangible observations and experiences in abstract and intangible ways and acts as an emotional magnet, pushing and pulling the reader in a particular direction based on the positive or negative correlations to the perceived message. A common, yet misguided, approach to analyzing literature is to identify a meaning. This meaning provides a single point— a center— from which a structure of understanding can be built.

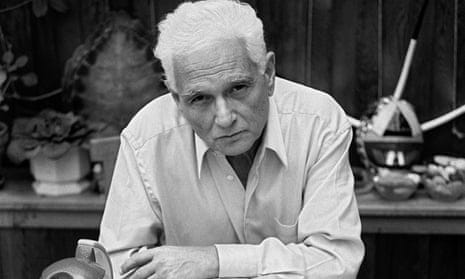

If one could forget the role of the critic (momentarily of course), one might preserve some of the motivations they have for reading in the first place. These are, among other things, to learn, to grow, or to imagine the unimaginable. Each of these reasons serve as catalysts for a subconscious reduction of the anxiety every self-conscious creature possesses. Jacques Derrida1 believes that the center is more than an orientation for structure and balance of a piece of literature. He argues that “above all [it is intended] to make sure that the organizing principle of the structure would limit,” what he refers to as the free-play of its structure. Derrida asserts that the center is, in fact paradoxical, and that “The center is not the center.” I want to echo this assertion and reaffirm its veracity.

“Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night,” by Dylan Thomas, is one of the most recognized and relatable pieces of poetry ever published. The death of a loved one is something that all must face, and the pain of the bereaved is yoked to the reader’s consciousness through the innate awareness of loss. No one is immune to the anxiety which loss fosters, and yet, we seek solace. I will demonstrate through a double reading of “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night,” that there are multiple, authentic, centers within the poem, which contribute to an equilibrium, of sorts, on a reader’s scale of hierarchical meaning, and in doing so, reaffirm Derrida’s assertion that “the center” is, in fact, not the center, but one of an infinite number of authentic counterweights which can be discerned through a close reading of the poem.

Historical context is not a prerequisite for one to connect with a poem nor is it necessary to discern meaning, however, history can offer tangible insights into some of the emotional experiences that shape Thomas and his penning of “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.” Thomas mentions several characters in the poem, most of which serve as archetypical figures. For example, wise men, good men, wild men, and grave men are named explicitly. However, his father stands predominant as the narratee and becomes the fulcrum which all meaning is balanced upon. David John (D.J) Thomas2, was the father of Dylan Thomas and is one of the more significant figures in Dylan’s life (Ellis). D.J had a degree in English and was an educator. He took care to impart his love for language to his son and made sure Dylan had access to his study and personal library, which included a “rich and up-to-date collection” of poetry (Ellis). D.J was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1933 and was subsequently forced to retire from teaching. He would combat the cancer diagnosis with rest and radium treatments for almost two decades, but in 1950 his health began to deteriorate rapidly. D.J chose to spend much of his twilight with his son, Dylan, and they redoubled efforts to engage in a shared love for language and poetry. This would have been a particularly trying experience for them both. According to the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, a 1952 report looked at observation from nurses in the United Kingdom, and it revealed that there were “appalling conditions of suffering and deprivation among many patients dying of cancer at home” (Saunders).

In the last two years of his father’s life, Dylan would spend the mornings with him and write poetry in the afternoons (Ellis). Dylan Thomas composed “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” in 1947. However, according to Hannah Ellis, he continued to work on the poem during the time he spent with his father, and it would remain malleable until being published in an Italian literary journal in 1951 and included in a collection of Thomas’ poetry the following year. In a personal correspondence with Princess Marguerite Caetani, Dylan would confide that his father was losing his vision and offer insight into his emotional connection to the poem writing, “The only person I can’t show (the enclosed) poem to is, of course, my father, who doesn’t know he’s dying” (Ellis). This admission strikes a tragic and haunting chord which serves as pneumatic soundtrack for the dirge. Unanswerable questions arise. Did he express his thoughts or feelings to his father? Did he revise the poem to incorporate his father’s impending death? Did his father ever hear the poem? How did the fact that his father, a lover of poetry and language, rendered speechless, blind, and dying affect the poet? Why encourage anyone to rage, rage, rage against the inevitable when acceptance could bring solace?

Without access to other primary source material from Thomas, the answers to those questions would be mere speculation, though Thomas’ own end, disturbed and less than a year removed from his father’s, appears to answer at least some of them. The ambiguity surrounding the poem’s origins are for another to analyze— its meaning— its, so called, center(s)— that is where our task lies.

Before conducting a first reading, it is useful to consider the structure of the literature. “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” is a villanelle. This verse form originated in France and consists of five stanzas, each of which containing three lines, and concluding with a quatrain. The first and third lines of the first stanza are present in the following as an alternating pattern, and the pair form the final couplet in the quatrain. The rigid structure to which Thomas commits this poem, directs the reader’s attention to the hierarchical forces competing for position as the poem’s center, that is to “go gentle into that good night” (1) or to “rage against the dying of the light” (19). In other words, an acceptance, or a resistance to death.

Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night

Dylan Thomas 1914 – 1953

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

An initial close reading establishes a hierarchical scale in which weight favors an acceptance of death as being a good thing. Though the first stanza briefly supplies a counterweight for an opposing meaning, the first line of the second stanza acts as tare and increases the precision of the initial argument. Additionally, Thomas’s speaker, the son, introduces the reader to the first archetype, wise men. “Though wise men at their end know dark is right,” (4) offers darkness as a symbolic representation of death. The symbol for death is transformed into a metaphor by incorporating an ethical position that establishes the poem’s center as one which accepts death as good. In this case, by knowing that “dark is right,” (4) the metaphor is affirmed through the wisdom of the archetypical “wise men” (4). As a center begins to take shape, the reader in presented with additional arguments for the primacy that dying is good through the introduction of both, good and wild men. “Good men” (7) implicitly hold a position of goodness by way of the adjective provided to the narratee in the opening line of the third stanza. Regarding the latter, “wild men,” (10) the narratee asserts more goodness—greatness even—insofar as they “caught and sang the sun in flight” (7). Images of Helios, the Sun-god, are conjured, and whom but the greatest of men could catch a God? Whom but the wildest— the greatest— would dare sing of it?

Thomas goes on to employ irony with the narratee’s introduction to the final archetype, grave men, in the fifth stanza and offers the reader insight into his personal life with uncanny similarities between the grave men and his actual father. “Grave men, nearing death, who see with blinding sight,” (13) is demonstrably similar to D. J. Thomas’ state of health. He was, in fact, dying and going blind. The irony of “Blind eyes,” (14) “who see with blinding sight,” (13) softens the negative connotation associated with an absence of sight. “Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,” (14) uses inspirational imagery and simile to capstone a message of the inherent goodness of death. Taken as a whole, Thomas’ use of positive archetypes, metaphors, symbolism, and simile weigh heavily on the hierarchical scale for a center which posits that dying is a good thing and that it should be accepted, free of resistance and absent despair.

With a center recognized, Derrida warrants more consideration. His theory does not invalidate the authenticity of a perceived center where acceptance of death is (or at least, can be for some) a good thing. On the contrary, Derrida’s theory simply states that this meaning is not—cannot be— the center, because “the center is by definition unique.” (Derrida) A second close reading reveals another, equally authentic meaning which can be perceived by the same reader as a legitimate subsequent center, thereby substantiating Derrida’s theory.

Whereas the first center leans towards an encouraging message for the narratee to accept death peacefully, a second close reading tips the scales in the opposite direction, unequivocally. “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night,” leaves no doubt as to how the speaker feels about the death of the narratee, or how the speaker would like for him to proceed into a good night (1). Despite death’s inevitability, and the peace which acceptance might offer the narratee (Dylan’s own father), the poem pleads for the narratee to be resistant and even goes so far as to demand he forgo quietus, choosing a rage filled end instead.

The dirge begins with a demand for resistance by stating, “Do Not Go Gentle,” (1) even though the destination is acknowledged as a “good night” (1). Thomas gives little credence to the thought that old age is a signifier of achievement, choosing to suggest alternatively that “old age should burn and rave at close of day” (2). Burning and raving are verbs which are customarily associated with pain and anguish. As a villanelle, learned readers would anticipate the first and third lines alternating again and again. However, the layman is provided a glimpse of what is to come, a different meaning and center that will be echoed throughout the poem— death is bad and should be resisted.

Each of the aforementioned positive attributes are immediately countered with negative language increasingly desperate and ominous. In the second stanza, “Wise men,” (4) who have the knowledge to accept death as “right,” (4) also recognize that “their words had forked no lightening,” (5) or more directly stated, lacked significance. As such, they choose to “not go gentle into that good night” (6). “Good men” (7) cry and recognize that their deeds were “frail” in the third stanza and choose to (8) “rage against the dying of the light” (9). Similarly, wild, and grave men “learn too late” and “grieve,” (11) and they choose to “not go gentle into that good night” (12) and “rage against” (15) death, respectively.

There is only one narratee in the poem, however, a significant, albeit slight, shift in the point of view can be observed with the first line of the sixth stanza. Between the first and 15th lines of the poem, the speaker is making a rhetorical case for resisting death. It is not clear if the speaker is, in fact, speaking to themself or another person. The 16th line demonstrates a shift in the tone and audience when the speaker states, “And you, my father, there on the sad height” (16). The speaker’s dilemma becomes obvious; his, or her, father is dying and everything said up to that moment was an argument to resist death. The tension between the “curse” (17) and blessing which the speaker “pray[s]” (17) for is drenched in “fierce tears” (17) that the father cries in anguish, and yet, the message, the meaning, and subsequent center, remain the same. “Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage, against the dying of the light” (18-19).

One can perceive and comprehend the validity of either argument for the meaning of Thomas’, “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night,” and in doing so succumb to natural tendency to identify a single center of meaning. Accepting death as good or resisting death as bad are both authentic possibilities because both are human responses to death and every reader brings their own imagination and life experience to the table. As such, one may construct their own unique meaning, their own center if you will. However, one cannot recognize both centers, and a third, or their own, without conceding that there are, in fact, many, many possible centers— that there are, in fact, innumerable centers.

Derrida explains that the center is a paradox, “within the structure and outside it” (Derrida). To focus on a single center is to make the meaning mutually exclusive and restrict other’s authentic experience and one’s own understanding. The scale of meaning is weighted to one side or the other based on the counterweights the reader chooses to apply. Through the deconstruction approach to a critical analysis of “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night,” one understands that an initial reading presents a center, a second reading presents another, a third presents yet another, and so on, and so on. Each close reading offers a different counterweight for the reader to apply. As Derrida states in the simplest of ways, “the center is not the center.” By utilizing his theory, the reader begins to understand that finding a center is not only impossible, but a diminishing force, working against their potential experience and enjoyment. It is the journey of discovering the unending-next center which offers the most joy in reading.

Editorial note: This essay was originally submitted in writing for EN-3350 at St. Mary’s University, San Antonio, Texas on 3 May 2023.

Works cited:

Derrida, Jacques. “‘Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences.’” Canvas, St. Mary's University, https://canvas.stmarytx.edu/courses/23606/assignments/319448?module_item_id=702683.

Ellis, Hannah. “D.J Thomas: The Man That Introduced Dylan Thomas to Poetry.” Discover Dylan Thomas, www.discoverdylanthomas.com, 8 Apr. 2020, https://www.discoverdylanthomas.com/d-j-thomas-man-introduced-dylan-thomas-poetry.

Murfin, R.C., Miller, J.H. (1996). '“Deconstruction and Heart of Darkness.” Heart of Darkness. Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism. Palgrave, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-14016-9_6

Saunders, Cicely. “The Evolution of Palliative Care.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Sept. 2001, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1282179/#ref4.

Thomas, Dylan. “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.” The Norton Introduction to Literature: Portable Edition, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2006, p. 555. Ed Booth, Alison.

Here’s an interesting article, published in 2020 by Brian Dillon in The Guardian, if you’re looking to learn more about Derrida. "An Event, Perhaps by Peter Salmon review – a timely biography of Jacques Derrida"

Here’s a great read from www.discoverdylanthomas.com, written by Hannah Ellis, Dylan’s granddaughter, which speaks to D.J’s influence on his son, Dylan. D.J Thomas: the man that introduced Dylan Thomas to poetry